The Riemann Hypothesis is an unsolved Millennium Prize Problem. It is a prime number theorem that determines the average distribution of the primes, telling us about the deviation from the average.

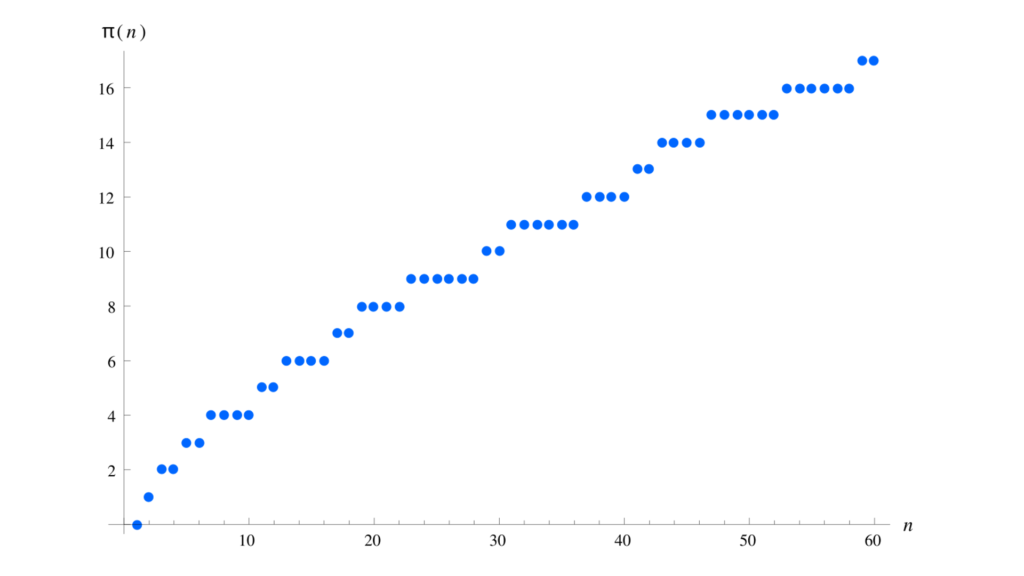

In the late 1700s, a young Carl Friedrich Gauss calculated massive tables of primes, going all the way up to 3 million, and looked for patterns. We can see the data that Gauss collected on the prime numbers by using something we will call the Prime Counting Function. The graph of that function will show us exactly where the prime numbers appear as the numbers get bigger and bigger. So, the graph stays flat until you hit a prime, and at that point it jumps up by one.

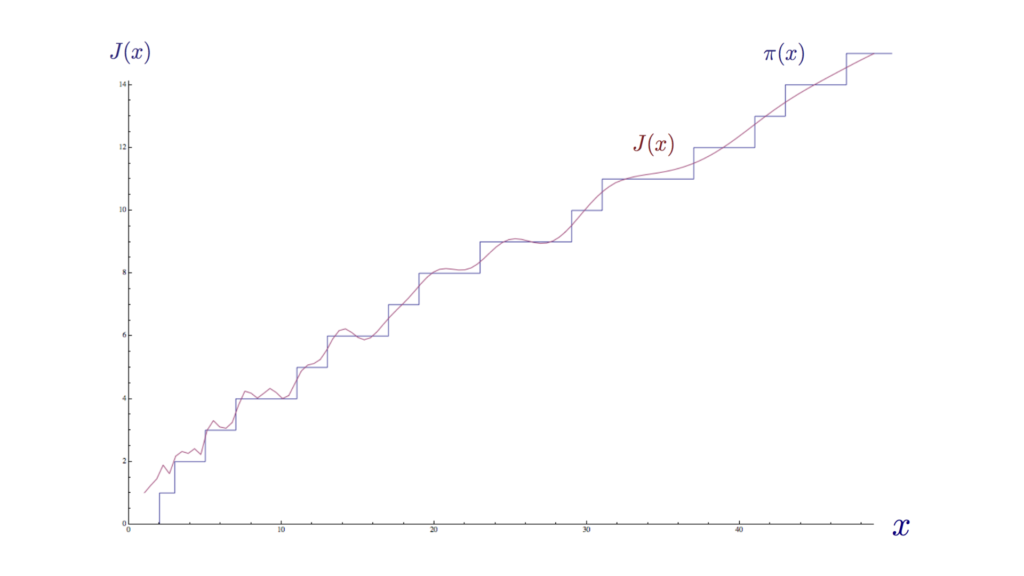

What Gauss noticed was that the graph of something called the logarithmic integral function, that is, a function whose gradient is 1/log(x), looked similar to the graph of the Prime Counting Function. A logarithm is a function that undoes exponentiation, much in the same way as division undoes multiplication. For example, 2³ = 8, log₂(8) = 3.

What Gauss imagined was that if you were a non-prime number, the proportion of prime numbers you would see is around 1/log(x). After Gauss formulated this conjecture, his student Bernard Riemann went on to do something incredible with it.

The Zeta Function

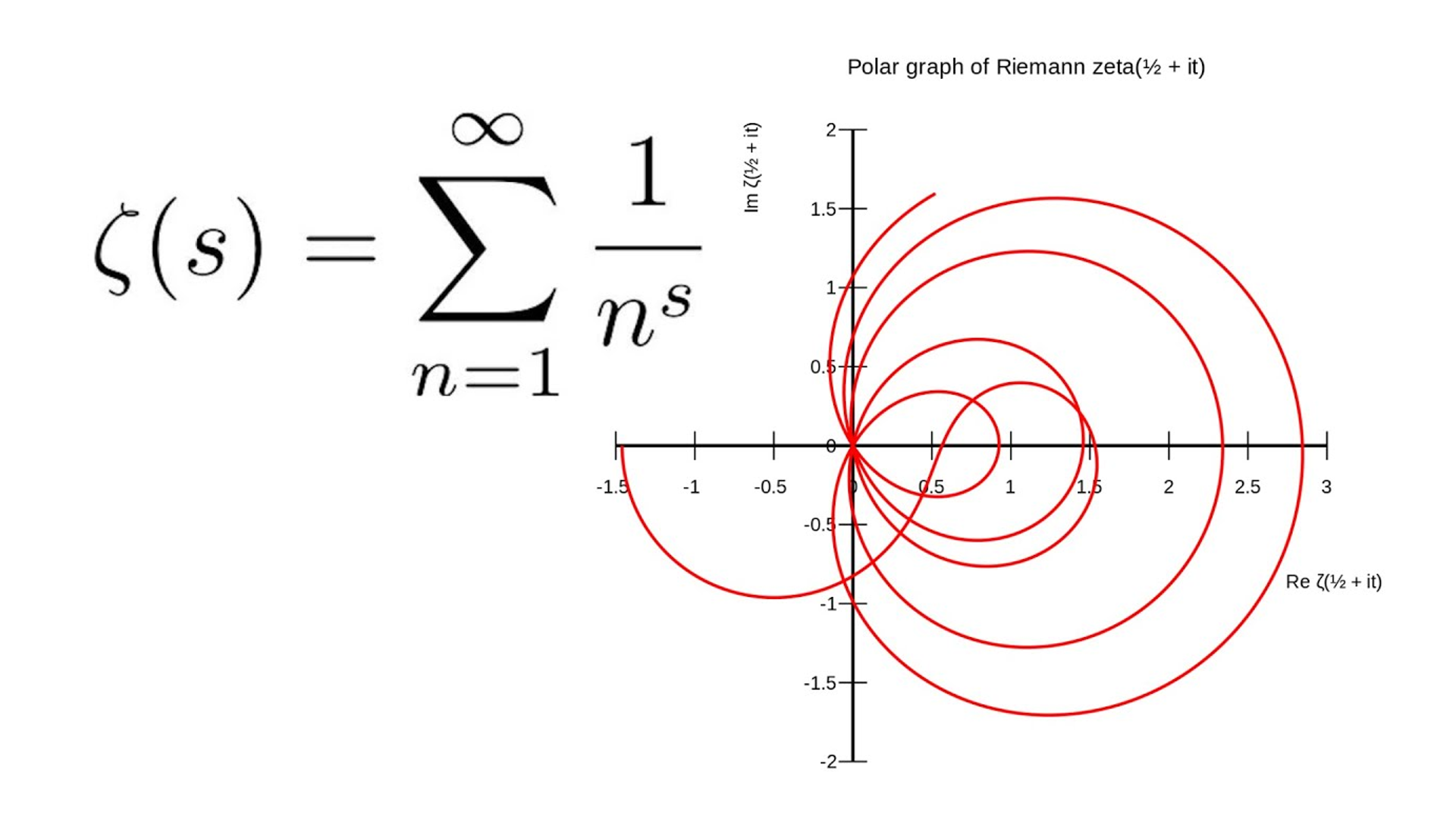

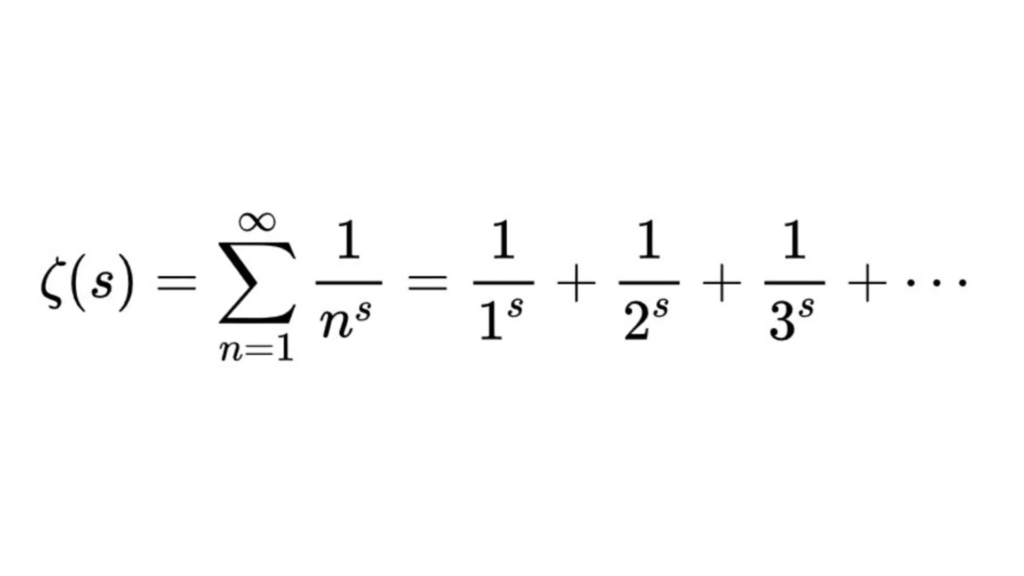

The Zeta function is a function useful in number theory for investigating properties of prime numbers. Written as ζ(s), it was originally defined as the infinite series.

When s=1, this series is called the harmonic series, which has an infinite sum. For values of s>1, the series converges (reaches a definite limit) to a finite number as successive terms are added. If s is less than 1, the sum is again infinite. The Zeta function was known to the Swiss mathematician Leonard Euler in 1737, but it was first studied extensively by the German mathematician Bernhard Riemann.

Riemann wondered what would happen if you allowed the Zeta function to take complex inputs.

A complex number is any number that can be written in the form of z = a + bi. This is said to be written in real-imaginary form where a is the real part of the number, and bi is the imaginary part of the number. The imaginary unit i is defined to be i=√−1.

When Riemann plotted each term on the complex plane, he found out that they form a beautiful spiral. However, terms less than 1 were not convergent. Riemann used a technique called analytic continuation, which allowed him to break open the hidden potential of the Zeta function. You can think of analytic continuation as a logical problem-solving method to extend the domain of a function. For Riemann to fill in the missing part of the domain in Euler’s data function, he had to create a brand-new function. This function would take the same values as the Zeta function, where they both converge, but it had to make sense everywhere else on the plane, too. So, there are two functions at work at once. The original Zeta function, which has limited scope and the Riemann Zeta function.

In the new territory that Riemann discovered, he found that suddenly the Zeta function could be seen crossing the origin. We call these places “Zeta Zeroes”. For example, when you input a negative even integer, the Zeta function equals zero. But we don’t need to worry about these so-called “trivial zeros”– it’s the non-trivial zeros that we need to talk about. Riemann identified that all the non-trivial zeros lie inside a single region called the critical strip. This is where the real part of s is between 0 and 1. Riemann proved that there are infinitely many zeros to be found in this critical strip. Riemann hypothesized that all the non-trivial zeros will lie on a single vertical line in the middle. We call this the “critical line” which is where the real part of s is exactly one half.

You might be wondering what the location of these non-trivial zeros has to do with prime numbers. Remember Gauss’ prime counting function. We’re going to slightly modify it. Instead of stepping up by 1 every time we see a new prime number, which we will call p, let us step up by log (p). Riemann found a surprising connection between this modification of Gauss’s conjecture and his new Zeta function.

Riemann was able to rigorously prove that if you add up all the harmonics of the Zeta zeros, all infinitely many of them, you get a perfect match to Gauss’ modified prime counting function. So, Riemann’s hypothesis showed that the distribution of prime numbers can be predicted and is connected to the location of these non-trivial Zeta zeros. Therefore, if the Riemann hypothesis is indeed true, it would tell us everything we could know about the distribution of prime numbers. Riemann was unable to prove the full hypothesis. There’s still only one way to be sure of it — rigorous, absolute, mathematical proof. And if you manage it, you could win a million dollars.