The Busy Beaver problem explores a deceptively simple question: “What’s the longest, most complicated thing a computer can do and then stop?” Here is the maths behind Turing machines and busy beaver numbers, to figure out what is the biggest value a computer can process without it being infinite.

The busy beaver problem is like a simple game played with just ones and zeroes, but it becomes mind-bogglingly complicated after just a few rounds. To understand how this game works, we first need to examine how Turing machines operate.

Turing machines

A Turing machine is one of the simplest, formal models of a universal computer and, as the name suggests, was developed by Alan Turing during the 1930s.

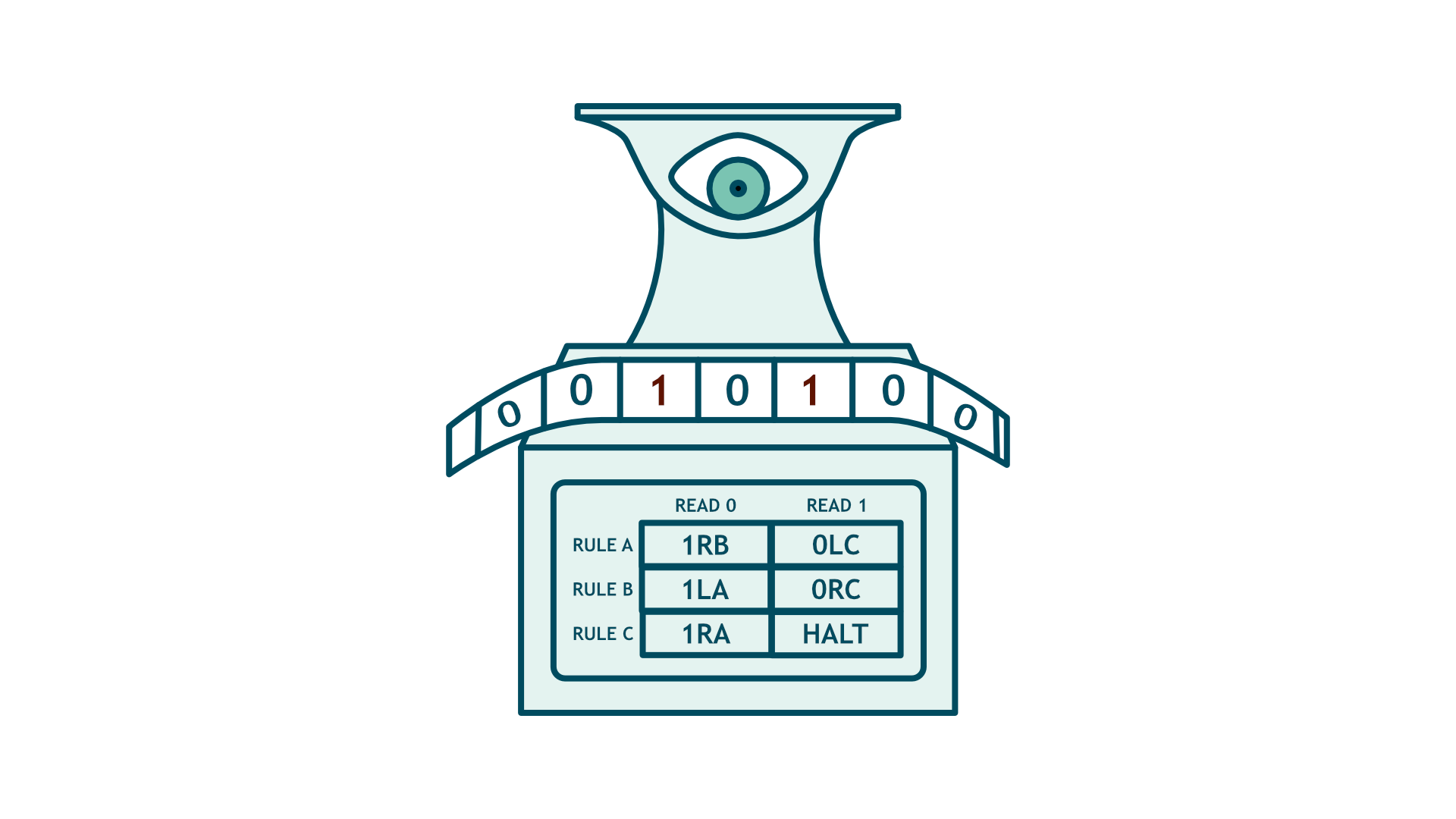

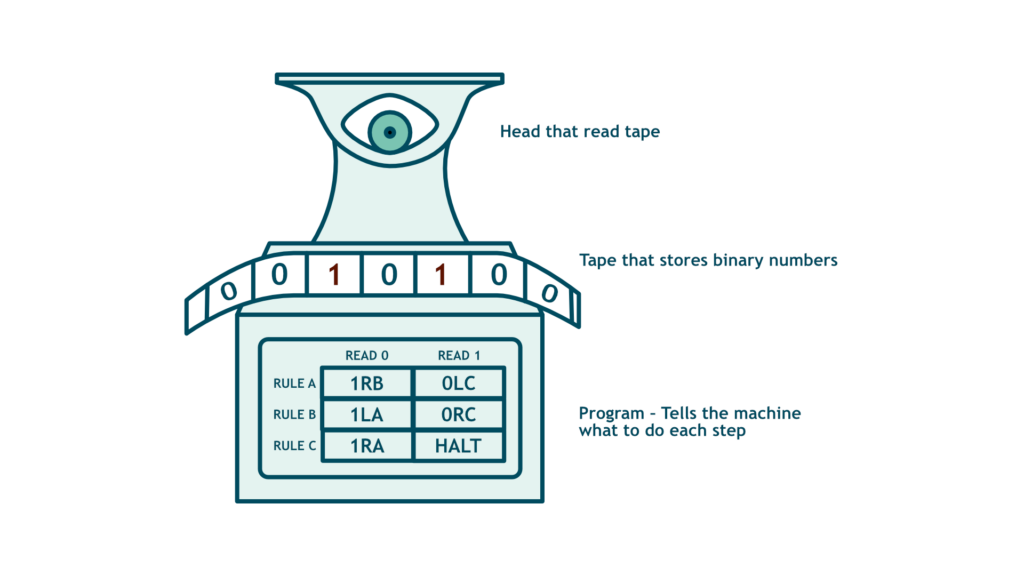

All Turing machines contain three components. An infinite tape that stores data in cells as ones or zeros. A head that reads the tape, writes a new number onto it, and moves the tape left or right. And a set of instructions, or a program, that tells the machine exactly what to do at each step.

Let’s look more deeply at the program – it is split into a table with rules (also known as states), each with an algorithm for if the head encounters a 1 or a 0 on the tape. It consists of 3 parts:

- Whether to write a 1 or a 0: denoted by 1/0

- Whether to move left or right: denoted by R/L

- Which rule to move to next: denoted by rule number/letter

Busy Beaver Problem

What the Busy Beaver problem tries to do is find the Turing machine of a certain number of states with the program that has the greatest number of steps until it stops. A Busy Beaver Number would be denoted as BB(n) where n is the number of states in the program.

BB(1) = 1, as that is the most steps a Turing Machine with 1 state can compute.

BB(2) has a champion number of 6 steps, ∴ BB(2) = 6.

As such, BB(3) = 21, BB(4) = 107, and BB(5) – which was proved in July 2024 – is a whopping 47,176,870 steps!

This was done by sifting through 17 trillion possible combinations of states to find a champion with the most steps!

Our next frontier is BB(6) – a number so unfathomably large that it requires its own explanation. “mxdys” (someone who was instrumental in confirming BB(5)) wrote that instead of proving BB(6) via exponentiation (written as ), we would need to use a concept called tetration (written as ) in which where the exponent is also iterated creating a tower of exponents.

An explanation for this colossal growth of Busy Beaver Numbers ties into another interesting function in mathematics – The Ackermann Function.

The Ackerman Function

If you repeat addition, you get multiplication:

If you repeat multiplication, you get exponentiation:

If you repeat exponentiation, you get tetration:

(Knuth’s Up Arrow notation is used for tetration)

The Ackermann Function is denoted as A(n) and essentially climbs up this ladder of operations:

The first 3 inputs for the Ackermann Function are all below 30. But on the fourth input, A(4), the value soars to a number that is bigger than the number of particles in the observable universe squared factorial, a number with approximately digits!

Well, you might be thinking how the Busy Beaver problem relates to this. In a similar way that exponential growth proved BB(5) and tetrational growth could possibly prove BB(6), functions like the Ackermann Function could just lead us to prove numbers even bigger and closer to the edge of computable numbers like BB(7) and BB(8) – if that’s possible.

This leads us to another question: Why is the Busy Beaver Problem useful?

Uses of the Busy Beaver Problem

The Busy Beaver problem is highly useful in computer science and mathematics as a benchmark for measuring the absolute limits of computability, algorithmic complexity, and mathematical proof.

Key uses of the Busy Beaver Problem include:

- Solving Undecidable Problems: Simulating conjectures like Goldbach’s

- conjecture on a n-state Turing machine and analysing this data.

- Defining Limits of Computation: Helping to define the boundary between problems that are solved by algorithms and those that are not.

- Testing Mathematical Truths: Providing a method to test conjectures by exhaustion.

- Growth Rate Benchmark: The Busy Beaver function grows faster than any other computable function, serving as the ultimate standard for comparing the growth rates of other functions.

In conclusion, the Busy Beaver Problem could serve as a useful benchmark for other problems and conjectures, but it is, after all, itself just as hard to solve as some of the hardest open problems in mathematics it might help to prove.